Hamstrings are a funny muscle in that most of the time, people are overly concerned that they’re too short. “My hamstrings are so tight, I can’t touch my toes!” “I wish I could do yoga but my hamstrings are too tight!” These two things are commonly heard by yoga teachers everywhere.

I had a student today with a specific complaint: Pain up in the area where the hamstrings begin- the sitting bones. She came to me after class and said she felt point tenderness there, especially when she was running. More on her later.

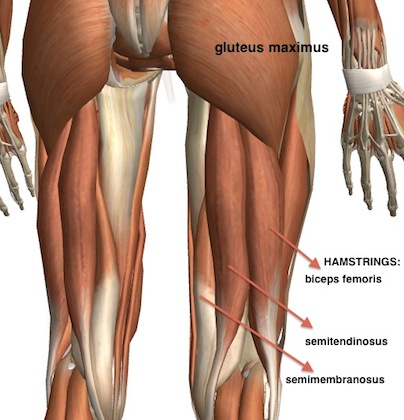

So, back to the hamstrings. Let’s talk a look at the hamstrings:

The 3 muscles in the middle of the image are the 3 sections of the hamstrings: semimembranosis, semitendinosis and the biceps femoris. Just to give you some perspective, you’re looking at the back of the right leg. You can see the back of the knee below and at the top, the whitish area, which is the origin of the hamstrings on the sitting bone, or ischial tuberosity.

Here’s another view:Â

So, because many students feel as if their hamstrings are too short, they come to yoga with one goal: MAKE THEM LONGER. This translates to an aggressive approach to any straight legged pose, including Downward Dog, Seated Forward Fold and Standing Forward Fold, among others.

If we approach our poses with one goal in mind and that goal exists on a continuum (meaning, “I want more of” or “I want less of,”) often, that leads to overdoing it. Infused with the “I’m gonna get there, come hell or high water and it’s yoga, so it MUST be good for me!” kind of energy, we tend to overstretch, thinking that’s the only way to do it “right” and get the desired effect.

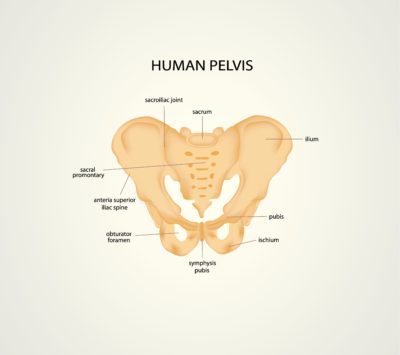

Keep this in mind: Your muscles, tendons, ligaments and other structures that maintain the shape of your body need to have a certain amount of tension in order to maintain that shape. If we were to overstretch the hamstrings, because they begin on the sittings bones and the sitting bones are on the pelvis, they could effect the stability of the pelvis. Think about it: If you have really “stretchy” hamstrings, your pelvis might tip forward or back with more ease ( not in a good way ) than someone with healthy tension in the hamstrings. Take a look at the pelvis from the front:

Here’s an image of the pelvis from the back:

Even though the point of this image is more focused on the sacroiliac joint, it does a good job of showing the pelvis from the back and the level position of the pelvis. If you look at the sitting bones at the base of the pelvis on either side, you can imagine that if the hamstrings were too tight, they’d tip the pelvis back and if they were too loose, they might tip the pelvis forward. And, because you have hamstrings in both legs, if they aren’t balanced, your pelvis would be slightly tipped more to one side than the other.

This all points to the importance of working more toward the “middle” and less towards “extremes,” even if we have all the best intentions in the world. This might mean bending the knees in forward folds; it could mean bending the knees slightly in Downward Dog. It might mean keeping a slight bend in the front leg in Triangle. Basically in any pose where the leg(s) are straight, it suggests that we resist pushing our legs totally straight, coming into knee hyperextension and instead, we bend slightly and engage the quadriceps a bit more to support the knee.

So, back to the student that approached me after class today. First of all, it’s important that we remember our role as teachers. We’re there as teachers, but not as physicians, nurses or physical therapists. We can’t see what’s happening inside the student’s body, so to a certain extent, it’s a bit of a guess as to what the issue could be. The first thing I try to do is get a sense of the severity of the sensation. Anything that’s sharp, consistent and causes the person to stop practicing is most certainly something that I’d suggest going to the doctor to get checked out in person. For things that are new, perhaps more on the “nagging” side versus sharp and “red alarm,” a fairly conservative approach is to suggest playing with some different variables to see if they have an impact (i.e. lead to some relief).

For something like this, the variables might include:Â

- Cutting back on running (or whatever activity is aggravating it, including yoga)

- Bending the knees more in any straight legged pose

- Refraining from approaching poses with an aggressive approach either way (stretch or strengthen)

- Massage the area (tennis ball, Yoga Tune Up balls are ideal)

- Work both strengthen and stretch movements: the most obvious ones for the hamstrings are Bridge for strengthening and Downward Dog for stretching, but there are lots of others as well.

Watch for what variable seems to have the best impact. Maybe cutting back is best. Maybe massage really helps. Also watch for an increase in pain after activity, recognizing that some discomfort might be a sign of healthy work but a dramatic increase in pain after activity might mean you need to cut back. I try to stay away from things like, ” Ice it,” “Take Advil” or other suggestions that are more in the medical realm (even if they’re common in standard conversation). How do I know if the person has an allergy to Advil? You get the point.

As always, suggest that the best first course of action is to get medical care for a check up and even if the student is not interested, it’s always helpful as a teacher to mention it.

I always advocate practicing more in the “middle lane” to allow the body to develop balance, rather than working hard to one end of the spectrum or the other. If you want to practice healthy for a long time, the more reasonable, conservative approach can be one way to do it.

Like to read about anatomy? Check out my free download below:

Interested in receiving a 3-PDF Teacher’s Yoga Anatomy Kit? Click here!

Thanks for reading!