I just recently sat for and passed the Certified Personal Trainer Exam and now am a CPT as well as an Experienced Registered Yoga Teacher. I’m really excited to pass the test and while it was hard, I was fascinated by the study material (books, online courses). It is a wonderful compliment to my anatomy-based teaching and brings a solid background in exercise science to this approach. (If you’re interested yourself in learning how to get your CPT certification, send me an email.)

I wanted to share with you some of the concepts from the personal training/exercise science world and relate it to yoga.Â

When we teach yoga, there’s always that first time we have students stand at the front of the mat, arms by the sides, ready to begin practice. “Tadasana” in yoga terms or “anatomical position” in anatomy terms, in any event, there’s a great deal you can tell about someone’s underlying musculature by watching their static posture.

Now in most instances, there isn’t much time to assess students in a group class but certainly if you teach privates, you’ll have more time to work with your client. In either scenario though, it’s helpful to understand a bit about the common syndromes in posture that are out there when it comes to teaching any kind of movement based exercise.

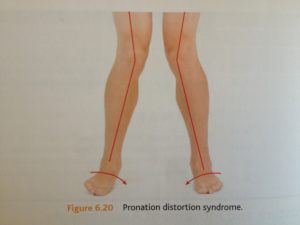

The first syndrome is called Pronation Distortion Syndrome. This might look like the student who is in Chair Pose with feet apart, but the knees are knocking towards each other:

For each syndrome, there is a list of muscles that could be overused or tight and muscles that can be underused or weak (or overstretched). Knowledge of these muscles can help you design a sequence that can help the student get more to “neutral.” It can also highlight some props that the student might use, for instance, squeezing a block between the thighs to strengthen the adductors.

In the case of Pronation Distortion Syndrome, the common culprits in terms of muscles that are too tight include the muscles of the lower leg (gastrocnemius, soleus, peroneals) inner thigh muscles (adductors), outer hip muscle (tensor fascia latae), Hip flexors and the short head of the biceps femoris.

Lengthened muscles typically include the muscle in the front of the shin, anterior tibialis, the back of the calf, posterior tibialis, and the back and side of the hip (gluteus maximus and gluteus medius).

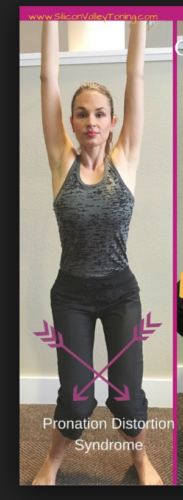

Here’s an image of what it might look like in Chair Pose:

Now, again, in group classes, there is not always much you can do to address this on an individual basis. You could suggest students’ bring their feet together. You could also suggest they squeeze a block between the thighs, while keeping the feet, knees and thighs hip width apart. But in any case, it can be helpful if not important (or at least interesting) for you as a teacher to have an idea of what might be going on underneath the skin when you see a presentation like this.

Teaching yoga from an anatomical perspective is always a balance. So, I must stress that we’re not talking about judging, nitpicking or taking the spirit out of the practice. But we are talking about helping people find a more healthy alignment in their body, both on and off the mat.

I realize this post is already quite long, so stay tuned for future posts this week about the other 2 postural syndromes!

If you enjoy reading about the anatomy of yoga, you’ll love my new book, just released two weeks ago called “Structure and Spirit: Moving Smarter Both On and Off the Mat”

You can get the book here.

And, for one lucky reader who has made it this far, I’m going to send you a book for a discounted price of just $20! The first person to email me TODAY will get the book for $20 versus $31.99 (list price).Â

Thanks for reading!