Whenever I write an article about yoga anatomy these days, I like to start out with a bit of a disclaimer.Â

First: I’m not a doctor (shocking).

Second: Everyone’s body is different (shocking again).

Third: Not every cue has to be applied the same way to every student (maybe a little shocking?).

I’ll admit I’m being a little sarcastic here but it’s for good reason. I want to be sure you understand the context within which I’m sharing this information (and any of the anatomy information I share in my courses, books, blogs, webinars, and more.) Â I want you to realize that although I have experience, my word is not fact and except for things that are factual, like we all have a femur, for instance, the application of yoga cues to anyone’s body is a particularly individualized thing. I mention this only because sometimes people read articles about yoga anatomy and they walk away thinking, “Ok, well I’ll never say that again!” Or maybe think that every forward fold is going to create a herniated disc. Or every “knee past the heel” in Warrior 1 is going to create unbearable pressure in the knee (more on these things below).

I get it. We want answers. We want to know how to teach correctly. We want to give effective cues. We want to help our students. Well, in order to do that, of course, we need (in part) a sound understanding of anatomy but also an appreciation for the nuances of it. The nuances allow us to appreciate not only each person’s unique anatomy but also acknowledge that at the end of the day, we’re working with limited information. We can’t see inside the student’s body to see what’s happening. We don’t know their health history. What we’re doing is providing general instruction based on a sound understanding of general anatomical principles and our experience. (By the way, this is why it makes sense to stick to fundamental poses versus the more complex postures that involve inversions, binds, etc. Again, to each his own).

So, having said that, when I teach anatomy, I love to address the “why’s” behind some common cues because I think that’s often missing when new teachers are taught. So many of us learned the cues without the explanation of the reason why the cue was helpful. “Why do feet have to be hip width? Why should hands be shoulder width in Downward Dog? Why should feet stay parallel in Bridge?” We often learn these without a real sense of why. Then, when a student asks us, we’re left to say, “Well, that’s how I was taught.” Bummer. (unless we did the research ourselves which is what I’ve done over the past number of years).

So here goes. See what you think:

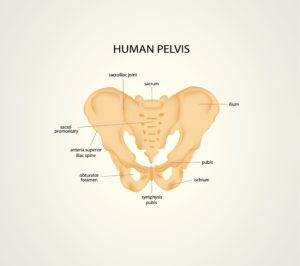

Feet parallel in Bridge and Wheel (in particular): This has to do with the most optimal position for the lower back while backbending. The challenge here is that the main muscle that creates the upward movement in both poses is the gluteus maximus (not minimus or medius- although the hamstrings help too). It has a dual function of also externally rotating the hips. If you externally rotate the hips while backbending, it can create some undue pressure at the sacroilliac joint. If you look at the picture below and imagine the hips externally rotating and the feet turning out as you backbend, you can start to see how you might feel a bit of a “crunch” in the lower back as the two halves of the pelvis “squeeze” towards the sacrum:

This also applies to the cue to “squeeze a block between the thighs.” The block is a reminder to keep the thighs parallel and encourages internal rotation and adduction of the thighs which will prevent the external rotation we don’t want.

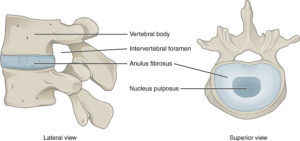

To “roll up to standing” or “come up with a straighter back/engaging the core.” This is a pretty common cue that gets discussed a lot. The concern with this one is that as you take someone in a forward fold (and possibly add in a lack of body awareness and/or any weakness in the core and perhaps even a pre-disposed back to spinal disc herniation – which you wouldn’t know about as a teacher), you can create a scenario for anterior spinal disc compression. It might not be an issue on that particular day, but over time, it could. Further, since most yoga classes offer a TON of coming up to standing from a forward fold, it’s further complicated simply by the frequency by which we do it.

To help you see this issue more, look below:Â

As the student “folds forward” the disc is compressed in the front (anteriorally) and therefore the disc material is pushed to the back (posteriorally). Eventually, the concern is part of the disc will rupture. Add in that the older someone is, the more natural degenerative joint changes there are and also if they have a job where they’re lifting heavy objects regularly, they might have a disc issue brewing already. My solution: Sometimes I talk about it in a bit more detail and compare the 2 approaches (full explanation). Other times, I simply say, “Stand up.” If you take the word “roll” out of the cue, it implies a more routine, regular action rather than using “yoga speak.” You could also add in something around “engaging the core as you lift” to support the spine with core muscles.

“Roll the inner eyes of the elbows outward” (in Downward Dog). I only started hearing this one a few years ago and I can say that it’s a little tricky to help students understand what you’re asking. If you use this cue, you might see people bend their arms and collapse towards the floor which is the exact opposite of what you want them to do! I like to walk them through this sitting, with their arms outstretched as if they were in Plank (but sitting up). I can then speak to the rotation of the humerus and the point of the cue without having them weight bearing on the arms.

The rationale behind this cue is that in most weight bearing poses on the arms, like Downward Dog, Crow, Plank, Side Plank and Table Top, for instance, you want to create a little external rotation through the shoulders. If not, you’ll just be hunching while you’re leaning on your arms. Think about how you hunch over your phone. Your shoulders are internally rotating. Then complicate that by putting yourself in a yoga pose where you have to hold yourself away from the floor using your arms. You can start to see how that internal rotation will create that hunching scenario all over again. Who wants to hunch in yoga? No one!

So, we need to use some of the shoulder’s powerful external rotators. These are two muscles that in fact connect to the humerus and help rotate it outwards. These muscles are the teres minor and the infraspinatus (see them both below).

Because of their position on the BACK of the body, they help roll the shoulder OPEN or externally rotate it. In order to contract these muscles, we have to get some of that external rotation to happen even while we’re weight bearing. Since we can’t flip our palms upwards, which would really open our shoulders, we have to  keep the palms down but slightly roll the “inner eyes of the elbows outwards.” Try it. Sit down, stick your arms out in front of you, spread your fingers wide as if you were rooting into Plank. Turn your palms slightly outward and you’ll feel the muscles activate.

There are so many more cues out there but this gives you a start. For more, download my class on Vimeo where I share a lot of the anatomy behind the cues. You can download it for $10 here.

For more detailed anatomy training (and chances to earn CEUs), check out my online courses, which range in price from $10 to $214 by clicking here.Â

There are lots of free downloads on my website and free webinars you can watch as well. My most popular download is about how to build a yoga sequence. It’s right on the home page.

Thanks for reading!Â