Over the past several months, I’ve been writing my second book (currently titled) “Structure and Spirit.” This book will be an exploration of anatomical concepts applied to yoga as well as spiritual concepts that apply both on and off the mat. As part of my writing part 1, (the anatomy portion) I have been diving into source documents; primary sources of research information on anatomy in particular. I also just released my latest online yoga anatomy course yesterday on May 1st. If you want to take a peek, check it out here ( there’s discount code information at the end of this article):

Learn the Anatomy, Practice It, Teach It: 3 Yoga Sequences

One of the articles I recently came across is on the role of fascia in movement. I’ve been reading more and more these days about fascia, the outer layer of connective tissue under the skin and surrounding muscles. I thought that as part of my own research into the article’s contents, I’d summarize it for you and provide what I believe are its relevant points for us as yoga teachers. That’s my whole goal; Â to dive into the research to see what we can learn from science and apply to yoga.

The article is here and is called:

Now, if you’re already ready to click off this blog post because that sentence makes no sense to you, hold on! Let me break it down and tell you why it was interesting to me, as a yoga teacher, to find out more.

What this article title conveys to me is that this research suggests that connective tissue, like ligaments and fascia, are just as important in proprioception, or the sense you have of where your limbs are in space (think: I’m in Warrior 2 looking forward but yet I can feel where my back arm is in space). In fact, when you look up “proprioception” in Wikipedia, you find a definition that states:

“In humans, proprioception is provided by proprioceptors in skeletal striated muscles and tendons. ”

Note that there is no mention here of the role of fascia (connective tissue).Â

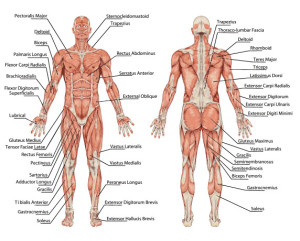

So, as a yoga teacher, it’s important for me to understand all the parts of the body responsible for movement. And most certainly, for proprioception.Â

So, in 2009,  Dr. Jaap van der Wal, MD, PhD, published an article based on his research on, of all things, the elbow joint of a rat as well as humans, to understand the role of muscles and connective tissue when it comes to movement. This was part of his doctoral thesis presented at the University of Maastricht (Netherlands) in 1988. There are a number of things he found and I’ll summarize some of these findings here for you and then pull it all together in what, I believe, are some applications for us as teachers:

What exists in the body is more of an “in series” arrangement between muscles and connective tissue where they work together to create movement versus an “in parallel” arrangement where they work completely separately.

To bring it into biomechanical terms, the muscles and connective tissues are organized with each other to enable the “transmission of forces” over the body versus the classical concept some hold, which is that ligaments are passive force guiding structures.

This approach to thinking about connective tissues as acting in parallel meant that when you did a dissection, you simply cut away the fascia to get to the muscle, because that’s where you thought all the action was!

Most anatomy books show muscles with the connective tissue fascial layer removed, thus more evidence that people did not think it played an important role in movement.

There are two kinds of fascia: that which fills spaces in the body between organs, for instance, and more importantly for us as teachers, fascia which serves as areas of insertion for neighboring muscle fibers.

In looking to biomechanics, 2 kinds of forces have to be transmitted over synovial joints (joints of movement): compression and tension. It has been thought that ligaments convey these forces only passively, meaning when they are fully stretched and loaded (think: yoga splits to your fullest degree). Before, it was thought that only muscles could transmit force even before they were at their fully loaded point. But his research was suggesting fascia had this property too.

So, in order to research this further, he honed in on the elbow joint in humans and studied it in humans as well as rats. He found that in the elbow, tensile forces were conveyed to the joint by not only the muscle but by the connective tissue.

He basically concludes, through his dissection, observation and testing, that the muscles and connective tissue structure (ligaments and fascia) are organized in series rather than in parallel, meaning they work together to create movement. To this point, he states: “in humans and in rats, no ligaments can be distinguished as separate entities. There is one joint stability system, in which muscle and connective tissue interweave and function mainly in series (collectively).

He then takes all this research and proceeds into discussing how it has implications for movement ( here’s where the yoga piece comes in). He goes onto say that:

“Fascial layers may thus play an important role in proprioception and nociception.”

He goes on to then look at joint receptors and finds that “it may be assumed that the joint receptors are also influenced by the activity of the muscle organized in series (there’s the phrase again!) with the connective tissue near those receptors.”

He concludes that proprioception is “not a matter of anatomy only but of also of architecture” and describes the architecture of muscles, joints and connective tissue. He found that muscle spindles (the sensory receptors in muscles) and golgi tendon organs (proprioceptive organ in a muscle) occur in muscular tissue areas in series with connective tissue rather than separate from them.

The overall conclusion is that the activity of a mechanoreceptor is defined not only by what it is and how it’s structured but also by it’s architectural environment.

So, what does this all mean to us as yoga teachers? Well, for starters, it suggests that our view of the body should be a bit more holistic and complete, which can be challenging, the more we study anatomy and look at the “parts” of the body. It also means that we should think of the ligaments around joints as being part of the action in terms of creating movement, not just structures that “do their job” when we’re fully stretched out in different shapes. I know for myself, studying anatomy often has me focusing on muscles as the “prime movers” not ligaments.

At the end of the day, we know as teachers we want to look holistically at our students. The more we understand the parts, often, the greater understanding we can bring to the whole.

Oh, and by the way, if you’d like to grab that discount code for the yoga anatomy online course, just join my mailing list between now and Saturday May 7th. I’ll be sending out the code every day in an email. When you join my mailing list, you also get a free yoga videos and teaching downloads!